Natural-hazard Insurance 101

(collected notes since I started my postdoc at the Institute for Risk Management and Insurance Innovation, UNC)

I’ve pulled these thoughts together to help make sense of how flood, wildfire, hurricane and other natural-hazard insurance actually work in the U.S. — why prices are changing, who sets the rules, and what practical options exist if you live in a risky place.

Big picture: why insurance looks different across states

A couple of headline facts that explain recent trends:

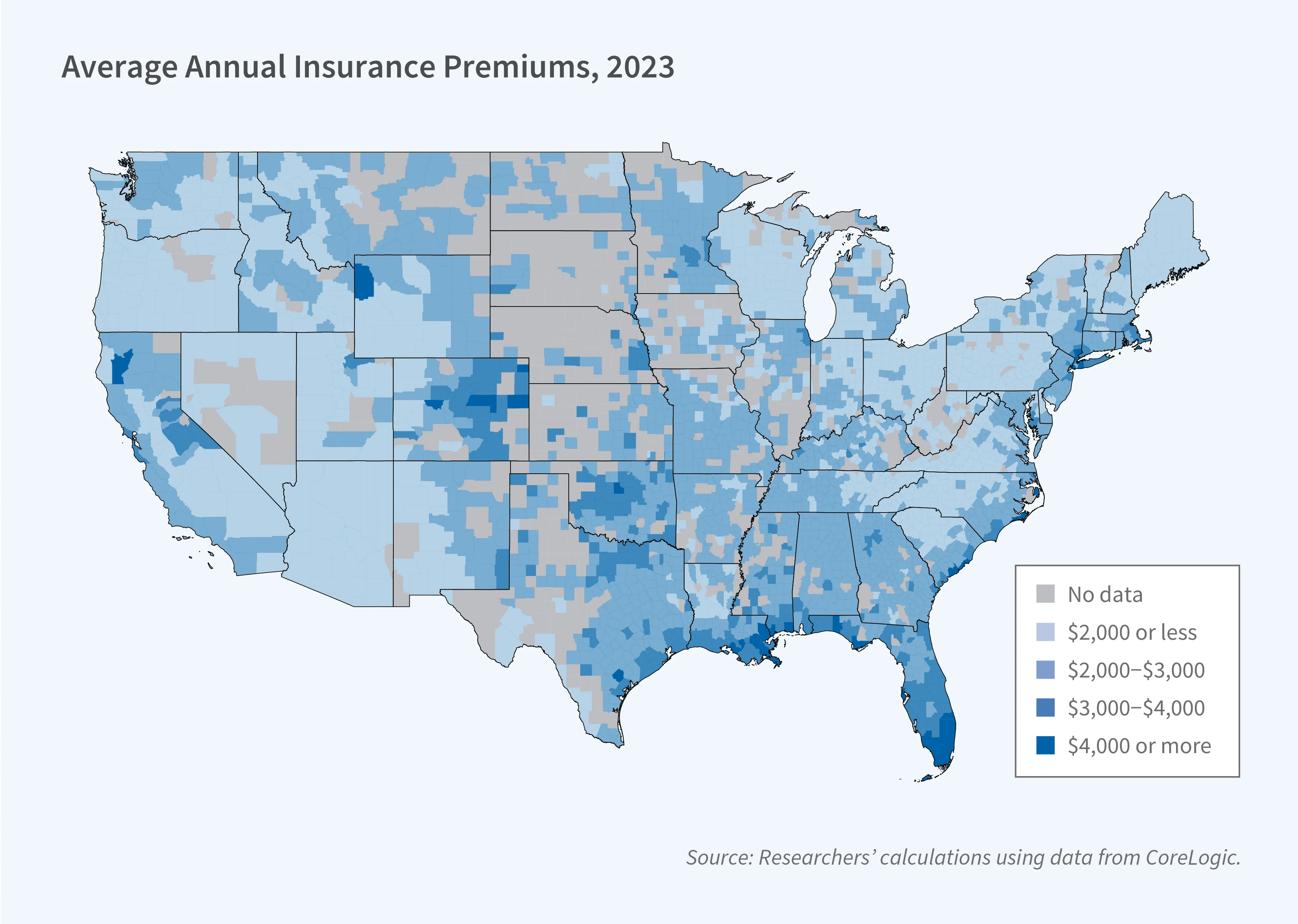

• Average property insurance premiums have jumped sharply since 2020 (roughly a 30%+ rise on average), with the biggest increases concentrated where hazard exposure is highest — coastal hurricane zones and wildfire-prone areas.

• One of the main drivers is higher reinsurance costs: insurers buy reinsurance to protect themselves from a single catastrophe wiping out their balance sheet, and when reinsurance gets more expensive, primary insurers pass some of that cost onto homeowners (see (Keys & Mulder), Property Insurance and Disaster Risk, NBER WP 32579).

Federal vs state roles

• Flood insurance is primarily federal (FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program, NFIP), and flood coverage is not included in a standard homeowners policy. If you’re in a FEMA high-risk zone, lenders typically require NFIP or an accepted private alternative.

• Other perils (wind, fire, hail, earthquake) are mostly handled by private insurers but regulated by states. States can also create residual-market pools (see examples below).

How that looks on the ground

• NFIP + private flood market (nationwide): NFIP remains the baseline for mortgage-required flood protection, but the private flood market has been growing as an alternative or complement to NFIP.

• Florida — Citizens Property Insurance: an insurer of last resort that often takes in homeowners who can’t find private hurricane/wind/homeowners coverage.

• Texas — TWIA: the Texas Windstorm Insurance Association provides wind/hail coverage for designated coastal counties where the private market withdraws.

• California — FAIR Plan: a pooled “last-resort” program that offers basic fire coverage for properties private carriers won’t insure (often wildfire-exposed homes).

• North Carolina has state programs that serve as backstops when the private market withdraws. Two state-run residual market programs: the North Carolina Joint Underwriting Association (NCJUA) — the state FAIR Plan that provides basic fire/property coverage where private insurers won’t — and the North Carolina Insurance Underwriting Association (NCIUA) / Coastal Property Insurance Pool (CPIP) that provides essential windstorm/coastal coverage for eligible coastal properties.

Key ways states differ (what actually changes by state)

- Which residual/last-resort programs exist and how big they are — some states have large, politically important pools; others do not.

- Cancellation / nonrenewal rules and consumer protections — some state regulators limit nonrenewals after storms or impose notice and rate-review requirements.

- Which perils are excluded from a standard policy — e.g., flood and earthquake are normally excluded everywhere and require separate policies.

- Flood mapping, mandatory-purchase zones, and mitigation discounts — FEMA flood maps (FIRMs) drive mortgage requirements; communities that invest in mitigation can reduce NFIP rates through the Community Rating System.

- Availability and price of private flood and catastrophe products — private options are much more available in some markets than in others.

Parametric insurance and catastrophe (CAT) bonds — new tools worth knowing about

Parametric insurance — the fast, objective payout

What it is: Parametric (or index-based) insurance pays when a predefined, measurable trigger is met — not when an adjuster assesses actual damage. Triggers are things like rainfall amount at a weather station, wind speed at a defined location, or earthquake magnitude within a defined radius. Why people like it • Speed: payouts can be disbursed quickly because they rely on objective measurements rather than slow damage inspections. That’s critical for liquidity after disasters. • Simplicity & transparency: the contract specifies the trigger and the payout formula up front. • Tailorable: parametric products can be written for specific perils and exposures (e.g., a farmer’s drought policy tied to accumulated rainfall). Main downside — basis risk • Basis risk is the mismatch between the index and the actual loss a policyholder experiences. For example, heavy localized flooding that damages your house might not be captured by the nearest gauge used for the index — so you could suffer damage but receive no payout (or vice versa). Where parametrics are used • Parametric products are popular for rapid liquidity, for agriculture (drought/heat), and for public finance (quick funds to repair infrastructure). They’re increasingly paired with traditional indemnity insurance to reduce overall response time and funding gaps.

CAT bonds — transferring risk to capital markets

What it is: A catastrophe bond (CAT bond) is a financial security that transfers insured catastrophe risk from an insurer (or sponsor) to investors. If a specified catastrophe event occurs (defined by a trigger), the bond principal is used to pay claims; if not, investors receive interest and get their principal back at maturity.

Why insurers & governments use CAT bonds

• Risk transfer / capacity: CAT bonds let insurers and governments access additional capital beyond reinsurance markets, especially for extreme events.

• Diversification for investors: these bonds are attractive to investors because catastrophe risk is largely uncorrelated with financial markets (until a catastrophe hits). That means higher yield potential.

Tradeoffs

• Cost: issuing CAT bonds involves structuring and investor return costs — not always cheap for smaller exposures.

• Trigger design & basis risk: triggers must be carefully designed (indemnity triggers, parametric triggers, or modeled loss triggers). Poorly chosen triggers create basis risk for the sponsor or investors.

• Complexity & legal/credit risk: documentation, collateral mechanics, and post-event verification add complexity.

How the pieces fit together

• Parametric insurance and CAT bonds are complementary tools. A government or insurer might buy parametric coverage to get fast liquidity and then issue CAT bonds to shift residual tail risk to capital markets. Innovations in parametrics (better sensors and modeling) are improving both the reliability of payouts and the triggers used in CAT-bond structures.